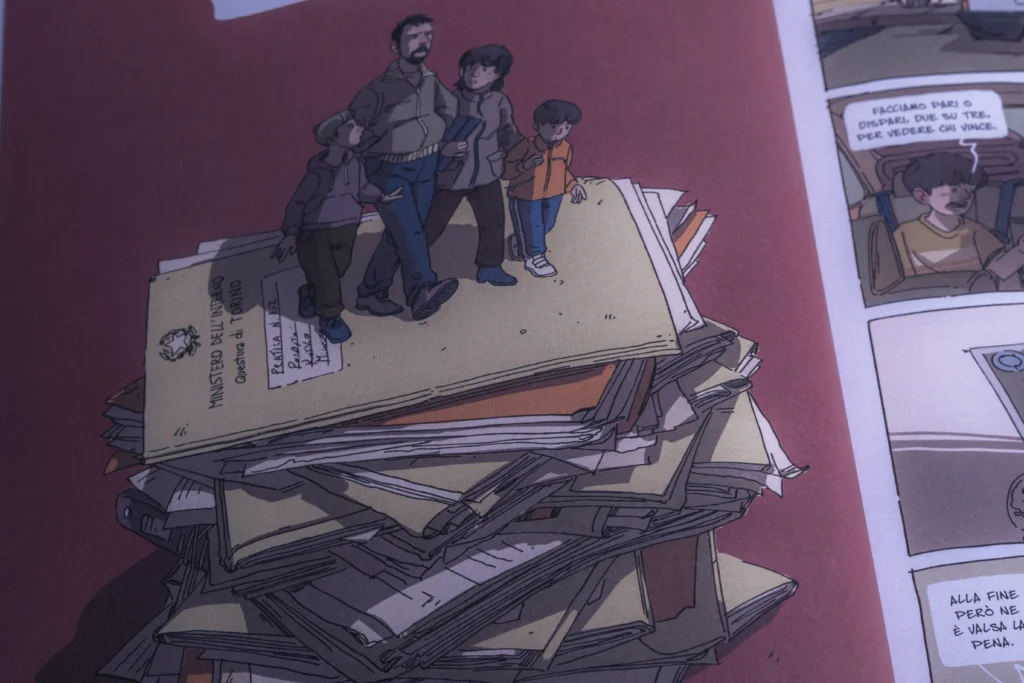

Boban Pesov defines “journey” as an undertaking that many have attempted but not all have completed: a hope for a better life.

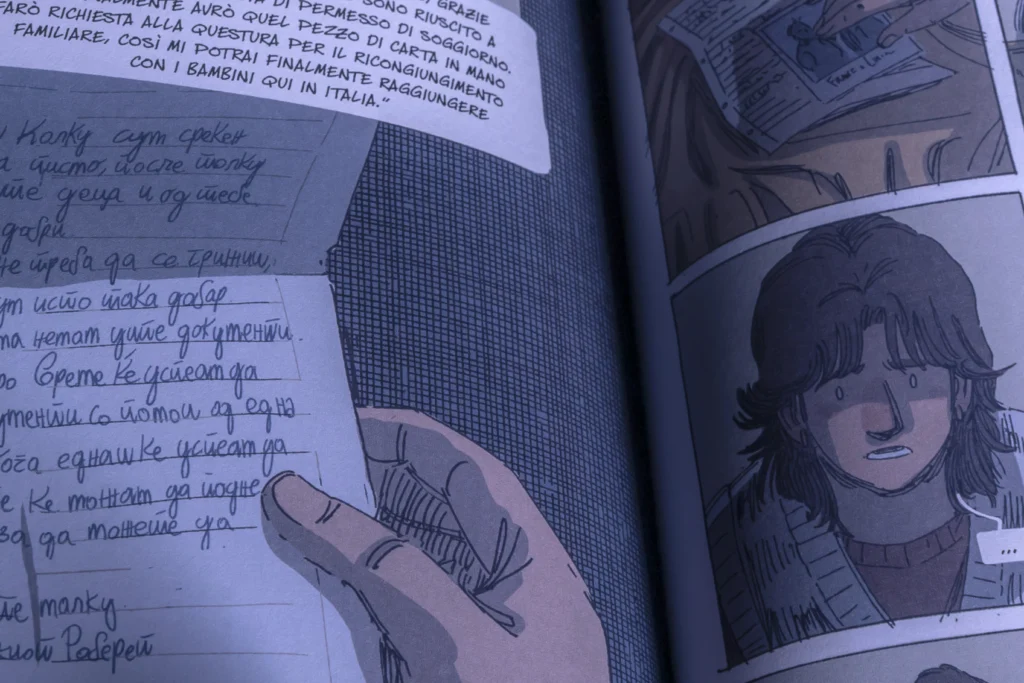

The journey that Boban tells us about is obviously also an emotional journey. It is a personal story divided into three different eras that span a period of 30 years. Through Robert’s memories and what his father Milan told him, the story is told by jumping here and there in time.

After the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the subsequent crisis that is taking place in the now former countries, Milan sets out in search of fortune in total secrecy. He crosses half of Europe following the so-called “Balkan route” to have a better future for himself and his family.

In a modern epic, Robert finds himself years later telling and retracing the journey, living it in reverse and with different borders. It is a story that speaks of family, suffering, and origins that mark people’s lives in one way or another.

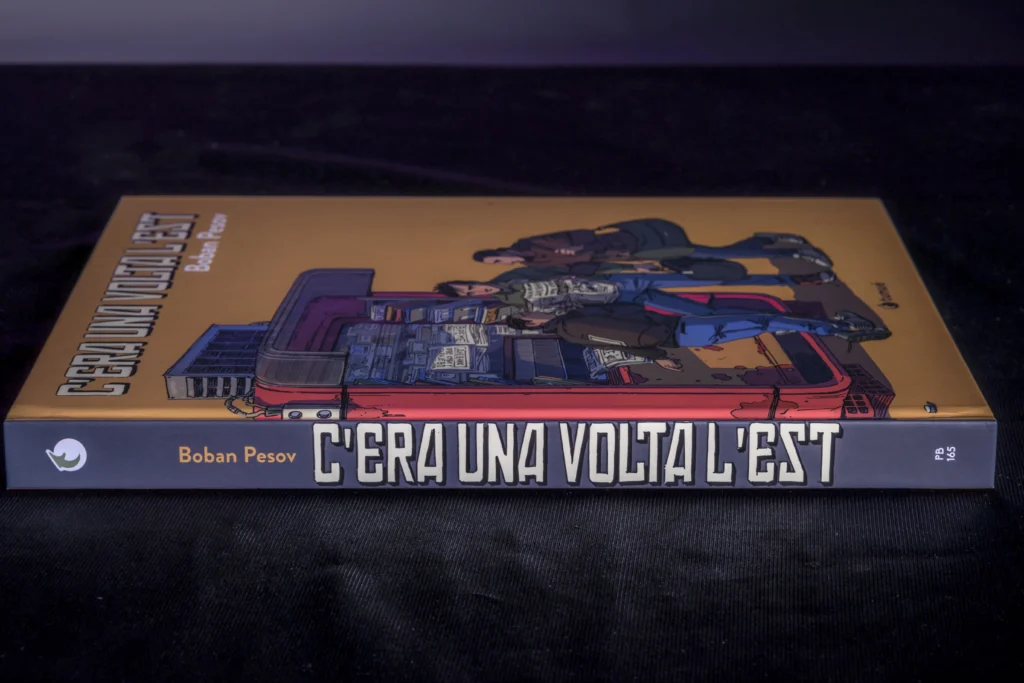

“C’era una volta l’Est” left us amazed, where we could talk to you until we’re sick of it. We could tell you about the title that recalls the great director Sergio Leone, moving on to the tiny details wonderfully illustrated by Pesov, continuing with the emotions that he conveyed to us, and then finishing with the classic tear.

But why do it ourselves? We had the pleasure of exchanging a few words in an interview with Boban and we bring you an excerpt.

I would start by asking how the book tour at fairs is going and how was your return to them?

Boban:

“… the return was a shock because I am no longer used to doing so many events one after the other, weekend after weekend… but it is going very well. The book is being liked a lot… for now I am super satisfied both with the feedback I am receiving from people who have already read the book, and obviously with everything that happens at a live level. So, when I go live to do the book signings, I really see a lot of interest.”

It’s been nine years since you published the video with your father telling his experience as an immigrant. “Once Upon a Time in the East” is obviously inspired by real life and facts, but how much of Boban and Stojan is there in the story? How similar or dissimilar are Milan and Robert to their real counterparts?

Boban:

“So yes. It actually started right from that video. Romantically, maybe, I try to take that video as a reference to say that maybe it started (all N.D.E.) there; maybe not exactly. It’s not that since I made that video, I thought every day that I had to make the comic, which in any case many years have passed. But actually at the time I made that video which also went very well, and where my father for the first time, publicly, without even too much fear, spoke about his experience as an illegal immigrant in the 90s. But I remember this thing; when he finished recording the video I said this to my father:

‘look dad, so many beautiful, interesting things. Maybe one day I could do something even more substantial, which could be a comic to tell…’

However, you know, at that moment I wasn’t clear about what I could do with that story that he told me. But today we’ve arrived here with a comic where there are actually many anecdotes inspired by my father. But there is also a lot of fiction, especially the figures of the two characters that accompany Milan… They are invented, they don’t exist, but they are a bit of a plastic representation perhaps of many young people who left with different ideas, with different ideologies, but they all left for a common goal; that is, to reach this destination. Which could be: France, Germany, Switzerland and arriving in another country and trying to find a better future for themselves and their family.

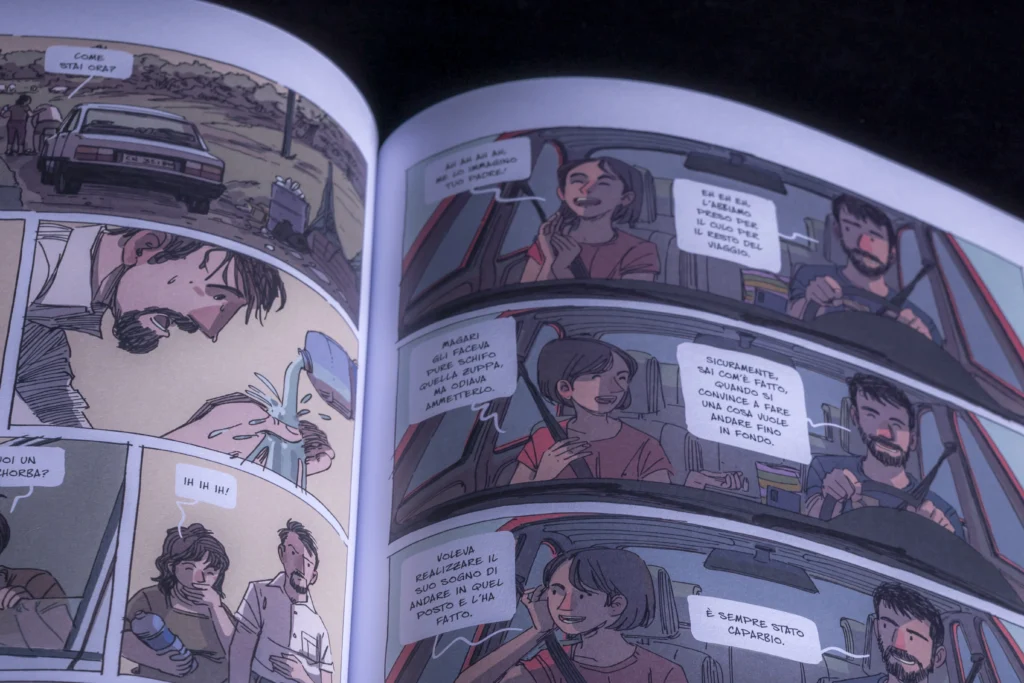

How much of my father is there in Milan? A little bit. In fact, Milan is the representation of how I remembered my father when I was young. But then you say ‘was he really like that?’ Maybe not, maybe some things are, even fictionalizing a story is also linked to how one imagines things: how one would like them and mixed with how they really are… This also applies to Robert who is the protagonist, who could be a bit inspired by me, but it’s different. In fact, I tried to accentuate some defects, which are defects that I have. And then maybe highlight also some merits, which are also my merits. However some events are actually fictionalized, they are invented to create also for the discourse of love, and of the love of the plot…”

You and your family have lived through the post-war period: the aftermath of the collapse of former Yugoslavia. How did you feel reliving the events when you wrote the story and what was your writing process?

Boban:

“Everything I know about the war is more for the fact that over the years, especially in recent years, I have started to study it a little, to know it better. It is from there, let’s say, I have always been fascinated by the tradition of Eastern Europe, the history, all the conflict between ethnic groups that have existed, and that have followed one another over the years… They have always fascinated me ; they are things that I have always wanted to rediscover and know a little…

And obviously here (in Once Upon a Time in the East N.D.E.) the recent history of the Balkans is resumed above all, therefore the war in Yugoslavia that I tried to tell more in the background but always through the words of the characters…

When I went to Macedonia for the first time, therefore the timeline of 2001, I vaguely remember some things. I remember above all the fears, the worries I had, of my mother, of the war that was going on along the borders with Albania and Kosovo. There were fears, the fears of facing customs for the first time; customs that had been in place for a few years because they were new borders after the war in Yugoslavia. So we didn’t know what the approach would be like, and how we would be treated. And I tried to tell this stuff through both images and through the characters’ words… Fears are always closely linked to memories that I have because really…”

I’m very curious to know who you had read this story first, even if it was a draft, and how that person reacted.

Boban:

“I have to be honest, I had a friend read it for the first time: Paolo Cellamare. For a clear reason: because Paolo has met my family, he came to my wedding, he knows something about my story, but he has always had an eye; an impartial judgment trying to shake off the fact that he is looking at a product of a friend of mine…

I don’t know if it was the first, the first. Well, the editor is actually the one who was following the comic for me, rightly so. He had to pester me and try to keep up with me. But the first person I said ‘I’ll have it read by’ was Paolo ; he came to mind immediately.”

Staying on the Cellamare theme, even if the link is a little languid, will you return to YouTube like the old days?

Boban:

* shakes his head vigorously from right to left and vice versa several times*

“Returning to YouTube means dedicating time to YouTube, that doesn’t mean that. Unless there is a project that can be linked to YouTube, but regardless of it…

For me, YouTube is now a tool with which you can spread content. In this case, I used it only to make a video, to promote my book and to tell a little about how the book was born. And that is one of the many channels, one of the many tools that I have at my disposal. Regardless of how many numbers that video makes, it doesn’t interest me. When it comes to publishing, first and foremost the product must always be valid, so that publishing houses can invest.

Tunué actually and independently invests whether I was a YouTuber or not, whether I was a popular author, or not; they were only interested in the product.

… So actually if I were to return to YouTube, I would return only to tell something. I would really like to bring a sort of reportage, I wouldn’t say documentary, but a story linked to “the game”, which is like that thing about the Balkan route that they call “the game”, about migrants who pass the Balkan route and live in very bad, horrible situations, also through testimonies of kids who have experienced it…

I used to plan posts during the week, I premeditated the tool so that I could somehow stay connected with people and Instagram in some ways surprised me. Not so much Instagram, the platform, but the audience that follows me on Instagram because I notice for example now when they come to fairs, a lot of them say:

‘I’ve been following your adventures for two years now, how you’re making the book.’

…and so it has become a sort of medium where I can also vent a little. Talking about the journey, the difficulties of making a book. And actually this wasn’t planned… It’s simply something that I did naturally. Something that came to me like that. Here and that’s how I understand the platform; something on which I can also talk about what I’m experiencing with my work… Something which made me very happy and YouTube did not.”

Concluding with the last question: do you already have a small idea for a future project, for a new book?

Boban:

“Well, well, let’s say that my desire to continue with Tunué is quite high for how I’m living now… Actually, yes, I have an idea. And I’ll just tell you this thing here:

‘the pleasure of having hatred. Let’s not use hatred because maybe there’s already too much of it at the moment. Having hatred towards someone, but for trivial things… a somewhat frivolous hatred… but what if this was the only hatred in the world? Maybe things would be better’

... if we’ve reached the point of worrying about things that are important like battles for equality etc. etc., it’s because we live well. And it’s a beautiful thing to live well. So, why not give other people the chance to worry about useless things in life? To worry about the trivial things of today: worrying about waking up, or about why maybe the girl you like didn’t like your stories. Because these are our worries. I wish we could all worry about bullshit, okay? And that’s what I would like to talk about in some way in the next book: to hate, to rejoice in stupidities, in the beauty of living in stupidities, but when you can do it. Because when something much more serious arrives that cuts our life short and doesn’t give us the possibility of thinking stupid things, then something is wrong. And there we really have to wake up, say maybe there is something that is not working. … I didn’t say anything ; I said a theme, a macro-theme that is too broad. An idea.”